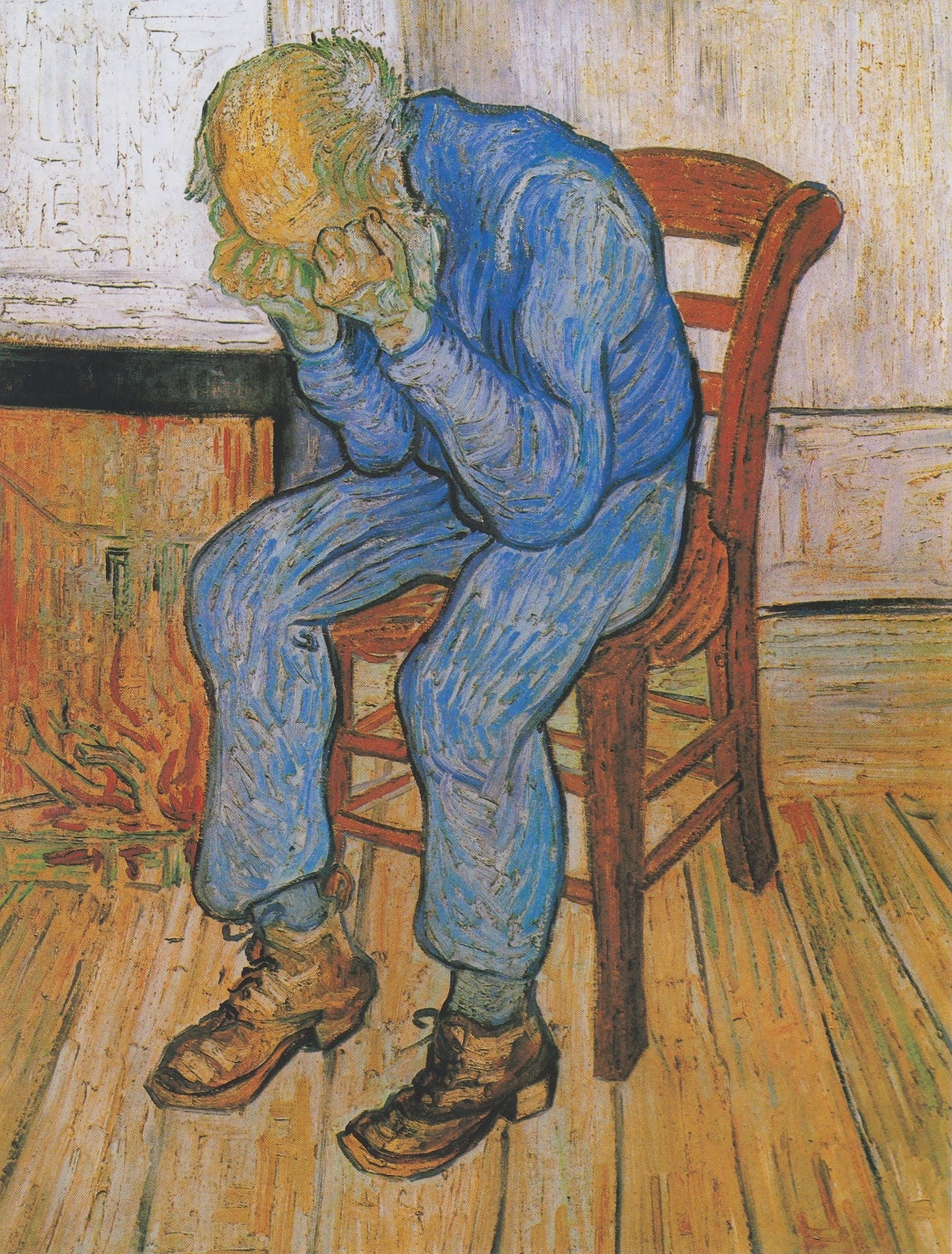

One morning about six months ago, I found that I could no longer get out of bed. My body lay fallow, and my mind simply repeated “I can’t do this anymore”, driving out all other thoughts except this ticker-tape repetition circling around my head. I was due to speak at a conference that week, I was due to go into work and see my friends, and I found that I could do absolutely none of it. I simply could not get out of bed.

As someone who has struggled with bouts of depression throughout my life, I knew the signs had been there for months, but I had buried myself deep in denial and had reassured those around me so often that I was fine that I had forgotten there was any other option. My definition of fine had slipped, slowly and gradually, from feeling generally okay and able to manage the uncertainties of life to well, I made a meal yesterday, so even though I feel completely hopeless and increasingly like a plane in a nosedive, and my body is screaming at me to stop, I must be fine, because if I’m not, I need to admit that something is wrong, and I cannot, by any means, do that. I had spent months talking to my manager about my slipping focus, decreasing my in-office hours due to a mysterious back pain, seeing fewer and fewer friends, all the while telling myself and anyone who would listen that I was doing pretty well, actually, convincingly enough that most people left me alone and presumed I was busy. For a time, it worked fantastically, until it didn’t anymore.

The interesting thing about catastrophe is that it often happens slowly. I don’t mean “it all happened in slow motion”, as people recounting traumatic incidents often describe, I mean that a catastrophe is usually the accumulation of factors that build upon each other until they reach a tipping point and - metaphorically or literally - explode into something that must be paid attention to. Often, these factors are permitted to pile up because people want to deny their existence, whether for selfish purposes (think the factory boss ignoring dangerous working conditions) or a complete incomprehension of how to deal with them. My own catastrophe hinged on incomprehension, and this incomprehension is what allowed me to ignore the glaring warning signs that something was deeply wrong; each warning sign presented a problem that I did not feel equipped to solve, as it would involve taking a step back from my life and realising, actually, the way I base my worth on my productivity, the way I obliterate myself to care for others, and the way I process overwhelming emotions by numbing them out are not conducive to a happy state of mind. Worse, after naming these factors, I would be required to change them, which was far more upheaval than I was prepared to endure. And so instead, I balanced each unfolding catastrophe like a spinning plate until the day they inevitably and irreparably came crashing down.

One of the hallmarks of being mentally unwell is spending too much time inside your head and too little time being present in the world. Now, don’t get me wrong, the cause of mental ill health is more complicated than this and often hinges on a range of socio-political factors - certainly for me, the cause of my poor mental health was a dizzying collection of interpersonal disasters, anti-trans politics, and contempt for myself - but the result of these factors can, in many cases, be boiled down to “spending too much time in your own head”. By the time I was unwell enough to be stuck in bed, I was spending most of my time in my own thoughts to the point that whole weeks were passing by with very little notice and, if questioned on what I had done recently, I would struggle to form a response that elided the truth - that I had been obsessively worrying about the future, the world, and my health and although I couldn’t tell you what I’d eaten for breakfast that morning, I could tell you about my all my personal fears and convictions that I had been rehashing and reworking for the last several months. I knew, on some primal level, that I needed to move my body, somehow get back into my body, and therefore back into the world, or I’d be stuck in my thoughts forever. So I did what any man in his 30s would do, and got signed off work and weirdly into the gym.

The first time I went swimming after I was signed off work, I moved my body like a reluctant child being cajoled into taking their medicine, slowly trudging my way from the changing rooms to the pool and then, agonisingly, down the steps into the tepid water. I was overcome with the feeling that the lifeguard and I were having a terrible interaction as I was alone in the pool, making the fact that I could barely swim the sole focus of attention. The lifeguard, looking at me in worry and confusion, remained quiet until I had completed a length and then asked if I knew swimming lessons were available. I kept floundering until I was physically spent (this did not take long) and then sat in the sauna, convincing myself that I was sweating out the mental illness. For a few hours, I thought the ritual had worked as I felt a wave of endorphins hit my pleasure-starved brain, eliciting a feeling that can only be described as similar to MDMA but more smug, because I had exercised rather than hurt my feet jumping up and down to nightcore remixes in someone’s basement. For a brief period of time, I was present in the world. The October heat seemed to be a blessing just for me rather than a sign of climate change, and I marvelled at how all I’d needed was half an hour in a swimming pool to fix what had been wrong with me. I told my manager I’d only be off for a couple of weeks, no need to reschedule my meetings - I was fine.

I was, obviously, pathologically not fine, and soon I was back in my head, looping over negative thoughts and catastrophic fantasies. I began to chase the brief post-gym high by going swimming and lifting weights nearly daily, living for the hour of endorphin-soaked normalcy that followed a good workout session before it all crashed into misery again. I could run a 10-minute mile, I had visible abs for the first time since I was a teenager, I had a snatched waist, and I was consistently Googling tips for handling suicidal ideation. I posted a topless photo to my close friends Instagram stories captioned “Physically the fittest I’ve ever been, but mentally? …Well, that’s one for the philosophers :)”. These were not the actions of a well man.

Despite my slightly unhinged thirst traps, my sex drive was another casualty of my severe depression. It’s hard to want someone to touch your body (or even want to touch it yourself) when you spend so little time in it. The only time I was brought back into my body outside of gym sessions was through regular panic attacks where an ice-cold fear crawled its way into my chest and made my heart beat painfully fast while I sat, petrified, and waited for it to be over or paced up and down my bedroom, concocting situations where this bodily response would make sense, and then believing that they were occurring (perhaps I did have cancer, perhaps a nuclear bomb was falling, and so on). As I have written about before, my body did not feel like a consistently safe place to be, and so I tried to spend as much time away from it as possible except in the predictable confines of the gym. With one exception, the thought of someone desiring my terrified, tense and vulnerable body was unfathomable, and the motives of anyone who did want to have sex with me were suspicious - it seemed to me that the only way someone could desire me is if they wanted something from me, and I had nothing left to give. I stopped writing about sex, except in abstract, oblique ways, and felt like a fraud whenever someone mentioned my sex writing. Even my fantasies replaced me with someone else - a version of me that was happy, relaxed, and sexual, who looked quite different and behaved in ways I would never do. It was a fantasy of who I’d be if I’d never been hurt, and when the fantasy was over, I returned to myself and couldn’t imagine that I’d ever feel normal and be able to have sex again.

I did not gradually get better. I got slightly better, and then worse, and then after one bout of particularly frightening suicidal ideation in December, I began antidepressants. There is an expectation when one is mentally ill that you will get better if you do all the “right things”, such as exercise, meditation and seeing friends, and this was compounded by my paid sick leave being slowly used up. I had banked on being better after a few months because I had to be, because I had to go back to work and earn money to pay the rent; the prospect of simply not getting better and all of its financial ramifications were terrifying to comprehend. Eventually, I conceded that I need pharmaceutical intervention - something I had previously avoided as the most common kind of antidepressants (SSRIs) do not agree with me - and I was put on a tricyclic antidepressant with a warning that the side effects can be hard to tolerate. The first few weeks were, indeed, hard to tolerate: I was perpetually groggy and having minor hallucinations, like seeing fleas on my bed and the wrong reflection in the mirror, but parallel to these, I was laughing for the first time in months and experiencing - briefly and in small increments - joy. I was both hopeful and humiliated that the solution to my depression was taking a pill once a day when I had been working so hard to cure it through willpower alone. Willpower, in the end, kept my head barely above the water, while antidepressants allowed me to begin climbing out of the water altogether.

And now, here in the middle of January, I’m not going to tell you that I’m fine, but I am going to tell you that I can get out of bed every morning, and most days in the last fortnight have been pretty good, and I’m able to write again. I’m grateful for that. The medication has worked astonishingly quickly and there is a feeling of suddenly being jolted out of my thoughts and back into the world, as though being woken from a daydream by someone calling my name. I’m aware of my physical presence in a way I haven’t been in a long time, including the realisation that many of my clothes no longer fit me and I’d been so divorced from my body that I’d just been throwing them on every day without realising how much work my belt was doing to keep my trousers up. I’m aware of which muscles are tight or overworked, and where I’m in pain or feel particularly relaxed in a way that feels revelatory. It is difficult to explain being dissociated from your own body unless you have experienced it, but perhaps the best comparison is as follows: Imagine you are living in a house, and each day you wake in the bedroom, go to the bathroom, cook in the kitchen, and relax in the living room. For some reason, each day these tasks become more difficult and cumbersome, but you cannot put your finger on why, until one day you open your eyes and realise that the pipes have blown, the radiators are broken, and the electric was shut off some time ago, rendering you walking around in the wet, cold darkness, bumping against every piece of furniture and wondering why all of your food tastes bad, and you simply hadn’t noticed.

It is only upon becoming aware of these things that you can begin to fix them - some people live most of their lives in a dissociative haze, and it is a great privilege to be able to wake up and begin the hard work of rebuilding. I do not take it for granted. I described the sensation to a friend as sitting in the rubble of my life and deciding where to rebuild and where to start entirely from scratch - all I know is that my life must change, and I have to trust myself to figure the details out as I go along. Part of this is finding my way back to pleasure. In this I continually think about John Berger’s essay The Red Tenda of Bologna (one of my favourite essays of all time), in which he writes: “It’s the coincidence of opposites. Amongst martyrs, and in the pursuit of little refined pleasures, there is something of the same defiance, and of the same modesty. At a different level naturally. But the coincidence remains. Both defy the cruelties of life.” Berger is entirely correct about the importance of small pleasures, and this is compounded when you are fighting against a depression so powerful that, at times, ending your own life has seemed like a viable escape plan. Sometimes small pleasures are all we have to hold onto when the larger pleasures feel hopelessly out of reach.

I normally don’t believe in new year's resolutions, but this year is an exception. The timing of my depression, rather graciously, culminated in the end of 2024, abated at the new year, and as a result this January feels like sunrise in a way that’s rare for these dark months. My resolution for this year is to be in the world as much as possible, in whatever form that takes. I spent half of last year as though walking in a fog, looking at the world from a distance, and the delight of reentering the world - with all of its flaws and its pains - is too great an opportunity to miss. I do not believe that I have escaped suffering for the rest of my life but, perhaps like Berger, I do believe there is a spiritual importance to celebrating the small things. I wake up in my home, I go to the gym, I have good food to eat, and I write: this is enough. I am, slowly, coming home to my body and it has graciously tolerated my absence and allowed me back in. It’s early days, but light is coming over the horizon, and I plan to be here to watch the sun come up. I hope that you’ll be there with me.

Looking at Porn is written around my full time job. I hope you enjoy it. You can follow my Instagram here and you can email me at robinccraig@gmail.com if you like.

Really happy to hear you’re coming back to yourself :) probably one of the most eloquent descriptions of dissociation I’ve ever read, thank you

“It’s hard to want someone to touch your body (or even want to touch it yourself) when you spend so little time in it.” — this bit really struck a chord. Sending you love and thank you for sharing this ❤️