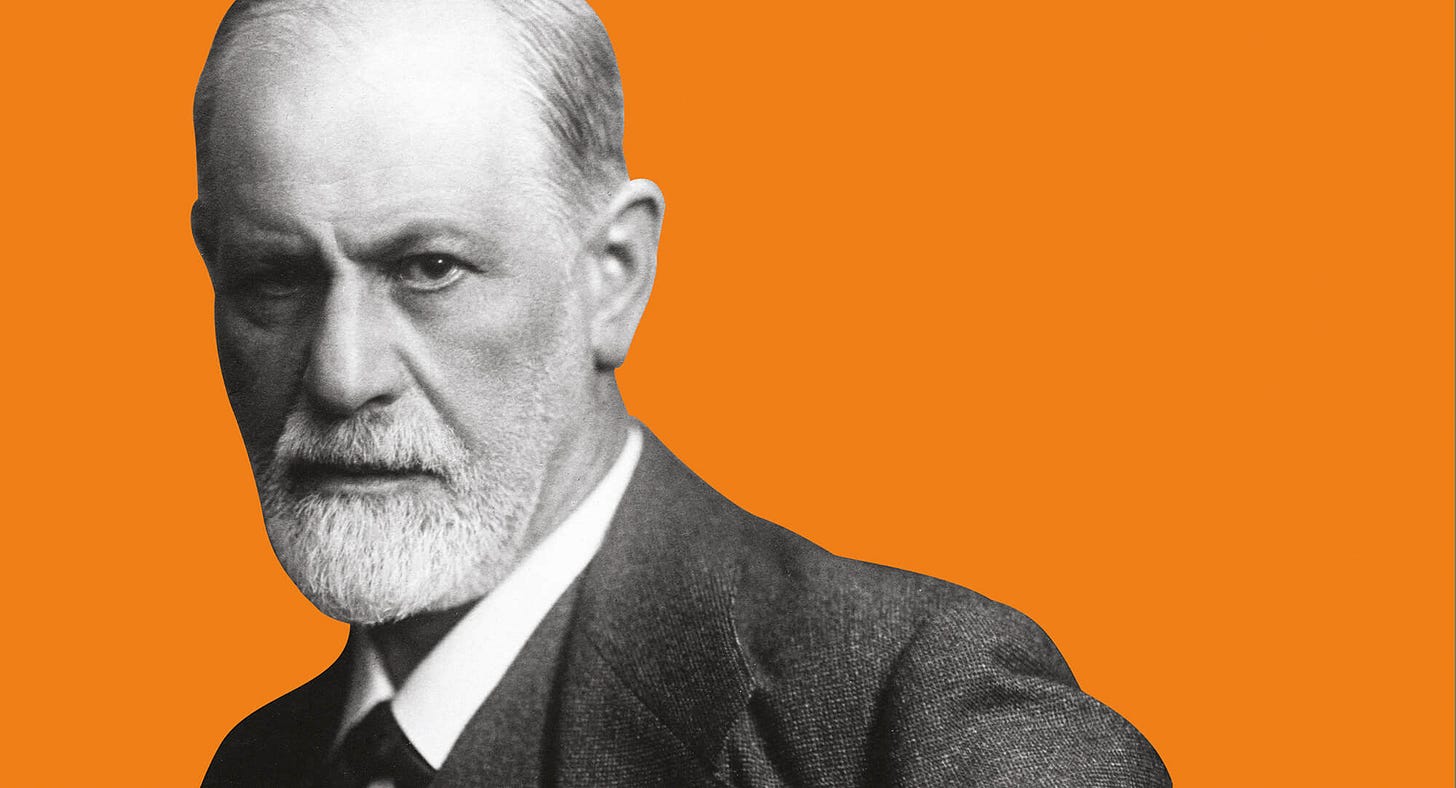

Pictured: Freud (my nemesis).

You may have noticed I didn’t post an essay in July. I’m on the final stretch of finishing my PhD and, subsequently, my workload has gone up and my energy levels have gone down. Until I complete my PhD in October/November I’ll be posting more casual thoughts and micro-essays that don’t require the research of longer pieces. …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Looking at Porn to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.